I was the Enterprise Vault ‘Evangelist’ in North America at Digital in 1998 before joining KVS as the Technical Director of North America. This is a history of Enterprise Vault and KVS written by Nigel Dutt, the founder of kVault Software (aka KVS). Nigel was kind enough allow us to post this history here.

Before KVS: 1997-1999

Conception

The genesis of Enterprise Vault was early in 1997. At that time Digital had decided to cut back investment in its own office product, ALL-IN-1 OfficeServer running on Open VMS, in favour of putting its weight behind Microsoft’s Exchange. Although of course this was not a happy proposition for the ALL-IN-1 engineering group based in Reading, it was arguably sensible for Digital in the long term. The plan was for the ALL-IN-1 team to be dramatically reduced following a major release and for the engineers to be moved to a yet to be defined new product that was to be some sort of add-on for Exchange installations. The original product we proposed was a large scale, searchable store for unstructured information, harnessing Digital’s own Altavista search and various Digital storage technologies. As originally presented it had various target scenarios including email archiving; however, one of our product marketeers, who had just returned to Digital from a role as an early Exchange manager opined that the email archiving target would be worth pursuing in its own right. So in May we made the “big pitch” to the relevant funding SVP with a product called “The Information Warehouse”. The proposition was for a central, searchable, scalable and cost-effective archive repository for email collected online from multiple email servers, the initial target being Exchange. The target drivers were storage management, regulatory retention and knowledge preservation. We got the go-ahead for this and the development project started, using the engineers now freed up from ALL-IN-1 3.2, who all retrained for the NT (later to become Windows) platform. Quite early in the project we renamed the product to “Digital Enterprise Vault”.

A myth has occasionally arisen that somehow Enterprise Vault was derived from, or was even a rebadging of ALL-IN-1, but it was a ground-up brand new development on the Windows platform (then Windows NT) rather than OpenVMS. The confusion probably arose because the engineering team had all come from ALL-IN-1. However, what we did carry forward as an engineering team was the sort of process-driven engineering methodology that we had developed for ALL-IN-1 engineering (following the SEI Capability Maturity Model) as well as building translatability into the product from the start.

Birth

After the usual torrid software development cycle and quite a long struggle to get some intransigent bugs out of the major beta test at Goldman Sachs, the product was finally released to manufacturing late on Christmas Eve 1998, if for no other reason than that the engineering team wanted to join their families for the holidays. By the time of shipping, Compaq had acquired Digital and so the product actually went out as “Compaq Enterprise Vault V1.0”. Initially the Vault only addressed mailbox archiving because Exchange journaling hadn’t shipped at the time, but that major feature was added to the Vault in a point release shortly afterwards, once the Exchange feature had shipped.

After the usual torrid software development cycle and quite a long struggle to get some intransigent bugs out of the major beta test at Goldman Sachs, the product was finally released to manufacturing late on Christmas Eve 1998, if for no other reason than that the engineering team wanted to join their families for the holidays. By the time of shipping, Compaq had acquired Digital and so the product actually went out as “Compaq Enterprise Vault V1.0”. Initially the Vault only addressed mailbox archiving because Exchange journaling hadn’t shipped at the time, but that major feature was added to the Vault in a point release shortly afterwards, once the Exchange feature had shipped.

During this time we also designed a spin-off product called “Enterprise Vault Mailbox Manager” (VMM). This was done in cahoots with Microsoft and was to be a “mailbox janitor” that cleaned out mailboxes subject to flexible policies. Microsoft had provided a “quick ‘n dirty” add-on to do this for the then current version of Exchange and it had proved extremely popular, so they wanted a “properly engineered” version of it for the next version but did not have the in-house resources to do it themselves alongside their work on the main product. Effectively it was a cut-down client and policy administration tool for Enterprise Vault but without the back-end archiving services, so older messages could be deleted but

in cahoots with Microsoft and was to be a “mailbox janitor” that cleaned out mailboxes subject to flexible policies. Microsoft had provided a “quick ‘n dirty” add-on to do this for the then current version of Exchange and it had proved extremely popular, so they wanted a “properly engineered” version of it for the next version but did not have the in-house resources to do it themselves alongside their work on the main product. Effectively it was a cut-down client and policy administration tool for Enterprise Vault but without the back-end archiving services, so older messages could be deleted but  not saved. The agreement with Microsoft was that VMM would be an optional add-on to Exchange V6.0 and would accompany that product when it shipped later in 2000. We would supply it for free but, in Microsoft’s words, we would have “full bragging rights” to then promote the full Compaq archiving product to the customers. Of course this was the marketers’ dream – access to 100% of our target market with the distribution all done via Microsoft. What could go wrong?

not saved. The agreement with Microsoft was that VMM would be an optional add-on to Exchange V6.0 and would accompany that product when it shipped later in 2000. We would supply it for free but, in Microsoft’s words, we would have “full bragging rights” to then promote the full Compaq archiving product to the customers. Of course this was the marketers’ dream – access to 100% of our target market with the distribution all done via Microsoft. What could go wrong?

Eclipse

By August 1999, two point releases of the Vault had been shipped, twenty or so sales had been made and a number of pilots were under way. Then, following the usual early warning signs as Compaq cut down on the software side of the business, the product was cancelled and the whole engineering team was made redundant. The very next day we all stood outside and watched a total eclipse of the sun, which seemed somehow symbolic at the time. While most of the group went off on their gardening leave, a few of us stayed behind to produce an “unarchive” tool to enable the existing customers to restore everything back to Exchange from their Vaults.

Re-birth

While this was going on, and since the investment climate at the time was very good, we decided to pitch the Vault as a viable basis for a new software company. At the time the Vault was the only purpose-built email archiving product shipping, the nearest thing to a competitor being the UNIX-based Storagetek product, so we felt we had a strong proposition. One of the first people approached was Durlacher, who were at the time the hottest thing in technical venture funding in the UK.  They immediately went for the proposal and came up with the initial tranche of money. So, almost before we knew what had happened, we were starting a company. On November 9th 1999 kVault Software (KVS) was formed; the “k” being for “knowledge” which at the time was just supplanting “e” as the trendy company name prefix of choice. The company started with twenty two of the redundant engineers and two administrators. Nigel Dutt (CTO), Eileen Christie (VP Engineering) and Derek Allan (product architect) continued with the roles they had had in Compaq (and a lot more besides) and Edward Forwood of Durlacher was acting CEO. Unfortunately, Compaq played hardball and set a take-it-or-leave-it price of several million dollars for the IP, to be paid over four years, unlike other employee spin-offs who had only been charged a nominal amount. However, they were well motivated to please the existing customers, so when we started KVS we were hosted in the same desks at Compaq that we had just left, albeit with special KVS badged entry cards. On February 14th 2000 we shipped KVS Enterprise Vault V2.0 from those premises and shortly afterwards we moved to our own address at Winnersh Triangle, near Reading, and finally felt like a “proper company”.

They immediately went for the proposal and came up with the initial tranche of money. So, almost before we knew what had happened, we were starting a company. On November 9th 1999 kVault Software (KVS) was formed; the “k” being for “knowledge” which at the time was just supplanting “e” as the trendy company name prefix of choice. The company started with twenty two of the redundant engineers and two administrators. Nigel Dutt (CTO), Eileen Christie (VP Engineering) and Derek Allan (product architect) continued with the roles they had had in Compaq (and a lot more besides) and Edward Forwood of Durlacher was acting CEO. Unfortunately, Compaq played hardball and set a take-it-or-leave-it price of several million dollars for the IP, to be paid over four years, unlike other employee spin-offs who had only been charged a nominal amount. However, they were well motivated to please the existing customers, so when we started KVS we were hosted in the same desks at Compaq that we had just left, albeit with special KVS badged entry cards. On February 14th 2000 we shipped KVS Enterprise Vault V2.0 from those premises and shortly afterwards we moved to our own address at Winnersh Triangle, near Reading, and finally felt like a “proper company”.

As an aside, when looking for a home for us and the product in 1999 I approached Veritas, who replied “no thanks, we are planning to do our own thing” – something I reminded them of when they acquired us in 2004!

KVS: 2000-2004

Early Days at KVS

Unsurprisingly the customer pipeline that had been established at Compaq mostly evaporated as KVS started up. Instead of buying from a major multi-national, the prospective customers were being asked to put their faith in a small British-based start-up, and for the most part that wasn’t about to happen. However, we did make some very early sales, the first being to Libertel in the Netherlands who purchased in our first week of operation. They were followed as early adopters by Freshfields in the UK, Clearstream in Luxemburg, Shaw Cable in Canada and Jackson National Life in the USA, which meant that we were instantly a multi-national!

These early sales were all via Compaq, except for Freshfields that was a Resolution Systems deal. In our first month we also partnered with Essential Computing who we knew well from our Digital days and they organised our KVS launch in London in December 1999. This event then led to more early business through Essential.

Similarly, because of the uncertainty when we were first cancelled by Compaq, the VMM project with Microsoft fell through, so we missed what would have been a fabulous opportunity for a small company to kick-start the business.

We set up a technical support and sales presence in the USA almost immediately and our US HQ was eventually established in Arlington (Texas) if for no other reason than that was where our North Americas manager lived. Over time several home-based regional offices were set up around North America, in particular in the New York area, reflecting the strong financial sector business we were doing there.

Having started with the ideal situation (ideal for engineers that is) of being an engineer-only company, we and our investors knew that we would need to hire a CEO and then develop the sales and marketing functions, and that started to happen after a few months when we hired Mike Hedger as CEO and he in turn recruited the people to start the various sales and other field organisations.

KVS growth

Over its almost five years of life, KVS grew rapidly and consistently in spite of the problems of the dot com crash of 2000-2002.

- Revenue:In our first full year, 2000, revenue was just over $1m, and it grew consistently to $23m in 2003 and just before acquisition in September 2004 the quarterly revenue was $10m, implying an annual run rate of $40m. Over this time, as expected, support, training and consultancy revenue all grew on top of license revenue and were contributing some 30% by 2004. The direct sales/indirect-sales-via-channel revenue split was always fairly consistent at 50/50.

- People:Over its lifetime the company grew from just over 20 UK-based engineers to around 220 people covering multiple functions worldwide. Reading in England remained the HQ, where around half the company was based, including the entire engineering group. We had about 75 people in the USA and 35 in the various EMEA and Australian sales offices.

- Geographic Reach: As already mentioned, we sold in multiple countries from the start. We initially sold only English language versions of the product, but translated versions soon followed, with European first and later Asian languages. We aimed to have a US presence right away and the North American sales organisation was built up just behind the EMEA organisation and was around the same size. French and German offices were started early followed later by Australia, Netherlands and Denmark. The Australian office dealt with Asia/Pacific in general. Roughly speaking there was a 40%/55% revenue split between USA/Europe with around 5% from the rest of the world. Reflecting that it was our base country, UK always contributed disproportionately well.

- Funding:We started the company with around twenty five well paid people in nice new premises, so our cost run-rate was significant from Day One. It helped that our office furniture was loaned to us for free by Compaq (in fact it was our familiar old Digital office furniture that had recently been replaced by Compaq and which, like ourselves, was redundant) and all of our Compaq computers were sold to us as a job lot. We quickly learned about the delay between orders being closed and invoices being paid, so we went through a cash flow problem early on and a couple of us founders even paid the salary bill one month when the board “invited” us to buy up our stock options. Having started with an initial $1m loan from our original investor, Durlacher, we sought our first round of venture capital funding in the summer of 2000. In this first round we raised $8.8m and we had two further rounds in October 2001 ($14.5m) and August 2003 ($17m) for a total investment of around $42m. Our investors were a mix of European and American venture capitalists (including Lehmans, Cazenove, Index ventures and Mosaic), which was a deliberate policy as we guessed that our likely future lay in American ownership or at least further investment.

Somewhat prosaically, one of the main underpinnings of KVS’s solid growth was “process”. A major advantage of the fact that we had initially developed the product within a large company rather than starting up with “two guys in a garage” was that we had taken a very formal process-oriented approach to software development and this approach was retained at KVS. For the same reason we also started with fully formed quality assurance and support functions who were a part of the development process. Yes, it would often frustrate sales people (who were probably thinking “I could knock that feature up over the weekend”) but the engineering process did produce a reliable product built on solid foundations. Equally, and probably to the surprise of the engineers, the sales organisation also started from Day One with a ready built formal and quantifiable sales process. This produced the required sales results and allowed accurate insight into sales progress and pipeline forecasting, even if the idea was alien to some of our more red-blooded salesmen.

In September 2003 we appeared in the Sunday Times “Tech Track 100”, which was their listing of the top 100 fastest growing technology companies in the UK. We just missed out on the medals by coming 4th with a year-on-year growth of 238.91%.

In September 2003 we appeared in the Sunday Times “Tech Track 100”, which was their listing of the top 100 fastest growing technology companies in the UK. We just missed out on the medals by coming 4th with a year-on-year growth of 238.91%.

Market growth

In retrospect, as good an indicator as any of our growth over KVS’s five years is a series of photographs that I have of our stands at various KVS Booth, Nice, 2000Microsoft Exchange Conference (MEC) shows.We started at Nice in the fall of  2000 where we taped our display boards to the supports of our minuscule stand and then picked them up and re-taped them the next day after they had all fallen off overnight. Our hospitality suite (and hotel for some of us) was a very nice old wooden boat hired to us at a discount by one of our investors and moored in the harbour.

2000 where we taped our display boards to the supports of our minuscule stand and then picked them up and re-taped them the next day after they had all fallen off overnight. Our hospitality suite (and hotel for some of us) was a very nice old wooden boat hired to us at a discount by one of our investors and moored in the harbour.

At this and the Dallas MEC that followed soon after, we found that the primary task in informal chats at the stand and at the more formal conference talks that I gave was to explain to people what email archiving was and why they needed it. Over the next couple of years the conversation steadily changed to “which archive product?” rather than “why archive?”. Of course if we’d had the time, money and inclination to go to fancy marketing courses or read the theory books we would have known that we were in fact “crossing the chasm” as we moved from innovation to mainstream.

As an aside, I remember a man from Enron asking me at our stand how our product could be used to ensure rapid deletion of email rather than long term retention, which at the time seemed unusual although it could actually be done. Then the following year the Enron liquidators were on our stand asking me if we could extract messages from old email system back-ups, which actually led to a service that we provided.

Over time our exhibition stands grew larger and larger and eventually became huge centrally located edifices visible from all corners of the exhibition floor and we also became major conference sponsors.

Over time our exhibition stands grew larger and larger and eventually became huge centrally located edifices visible from all corners of the exhibition floor and we also became major conference sponsors.

In the early years we specifically spent a lot of time working with the analysts in order to have them understand the email archiving market and in particular to validate and identify it as a business sector in its own right. Gartner was one of the first to recognise the sector and then to bless it by producing their first Magic Quadrant for it. KVS was the only leader in this and the following few Magic Quadrants, although other vendors subsequently joined it in the top right hand corner. Pretty soon all the major analysts were producing reports on the sector and predicting very significant growth figures for it. By the time we were acquired in 2004 the annual market was around $200m with strong growth predicted. By 2010 it was in the $2.5bn+ area and all the forecasts continued to predict strong growth, and that doesn’t include all the spin-off markets such as litigation support.

As the email archiving market grew, a new set of specialist companies such as Educom, IXOS, iLumin and Legato joined the fray early on, followed later by names such as AXS-One, ZipLip and Mimosa.

KVS Business evolution

There is a myth that regulatory driven archiving only came along later in the life of the email archive business, but in fact it was there from Day One as the SEC rules applicable to electronic communication were first published in 1997, and it was part of the original product proposition in that year.

There was also the Microsoft myth, or at least their official line, that the only need for third party archivers was for regulatory purposes, and they never officially recognised that the management of messaging system storage growth was an issue (or at least not until they themselves introduced archiving functionality in Exchange 2010). In practice we sold journal licenses from Day One but mailbox archive licenses were always the bread and butter of the business. During the life of KVS, mailbox seats sold were always around twice the number of journal seats, and in terms of revenue the ratio was more like 6 to 1. Just to clarify: in journaling, mail is moved into the archive as it is received by the system and before it gets to individuals’ mailboxes, so is a guaranteed way to capture all email, typically for regulatory-driven retention. Journal licenses are per user on the system. Mailbox archiving is tied to individual users’ mailboxes and is a way to move older messages out of mailboxes, optionally replacing them with smaller “stubs”. Again, licenses are per user.

However, increasingly, and especially in finance (our largest customer segment) and the legal and government sectors, regulatory retention became the “compelling event” that drove the sale, even though these customers tended to buy mailbox management alongside journaling. At the same time, high level customer meetings increasingly included corporate legal representatives alongside the usual IT people.

event” that drove the sale, even though these customers tended to buy mailbox management alongside journaling. At the same time, high level customer meetings increasingly included corporate legal representatives alongside the usual IT people.

As the product developed further, significant revenue earners were added. PST migration was added in 2000 and was always consistently successful, exceeded journaling revenue. PSTs are the personal quasi-archive files held on PCs and servers and their growth rapidly became as much of a problem as that of mailboxes. Compliance Accelerator, which enabled the monitoring and sampling of email within an organisation, and Discovery Accelerator, which enabled formalised searching for litigation support among other uses, were added in 2003 along with file system archiving and these all rapidly became strong earners.

A very significant development for a very small company in mid 2001 was being invited to join the alpha program of a then secret EMC storage product as the only partner product in the email archiving sector. The characteristics of this new object storage WORM device, which turned out to be Centera, were tailor made for our product and this technical relationship led to a very beneficial mutual business relationship.

Product Evolution

As would be expected, there was a significant program of continuing enhancement of the base products as well as the new licensed products mentioned above, and given the increasingly competitive environment, most archive products were following the same path. The initial PC-based Outlook client support was enhanced with functionality such as Offline Vault for laptop users, Outlook Web Access support and the web-based Archive Explorer. The product was implemented from Day One to be fully translatable, so foreign language versions (including Asian) were developed from an early stage.

Some of the overall development themes over KVS’s lifetime were:

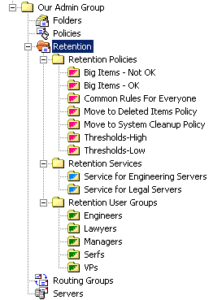

- Increasing reach:Evolving Enterprise Vault to being more of an “archiving platform” than specifically an Exchange email archiver. More archiving clients were added alongside the original email service so that the archive gradually became a repository for any and all “unstructured information”. The additional archive services included PSTs, public folders, files systems, SharePoint, Lotus, and SMTP mail. We held off publishing an API and developers’ kit because of the support implications, but this was exactly the sort of thing that would make sense as soon as a large company with the appropriate infrastructure took over the product.

- Lifecycle management:When we started out we often met quite an aggressively negative attitude to the idea of long term email retention such as “90 days and it’s gone”, but the tide then turned, especially in the face of increasing regulation and end-user demand, towards “keep everything forever”. Over time this simplistic approach became much more sophisticated and evolved into “lifecycle management” where aspects such as more selectivity over what was to be archived in the first place, categorisation of information going into the archive, how long to retain it, where to put it initially, when and where to move it subsequently, whether and when to delete it, all became archive management criteria.

- New devices:Initially the archive store was often CD or tape, but eventually these devices just about disappeared in the face of low cost disk storage, NAS devices and specialist WORM stores such as Centera. At the same time the concept of secondary storage movement was introduced so that archived items could after time be further migrated from one type of store to another more cost effective one. The natural progression now is to Cloud storage.

- Content exploitation:“There’s gold in them there archives” was one of our original archiving propositions; that is, “you need to keep this stuff because along with all the dross it also contains much of the intellectual property of your organisation”. However, other than the ability to search and retrieve the information we didn’t provide any further tools to exploit it. Then we developed more content-aware Products such as Discovery Accelerator (for litigation support, etc.) and Compliance Accelerator (for supervisory oversight) along with much better search and exploration tools. Again, offering an API in this area would be the future key to the growth of both in-house and third party content exploitation products.

Acquisition

By 2003, given the fact that the email archiving market had properly arrived and its forecast growth was very strong, it was not a surprise that some big name companies were looking to get into the business either by building or buying.

Around this time some of KVS’s competitors were already being snapped up, and in mid 2003 we flirted with some would-be buyers who had approached us. In particular we talked in detail to Veritas, but they decided to build rather than buy, which was something that was very obvious to us when their technical team came over to see us; it felt much more like “deep digging” than “due diligence”. We received offers from other companies in 2003 but none were acceptable at that time.

However, by mid 2004, we were almost in the position of being last man standing of the successful specialist companies and we were now competing with the likes of HP, Zantaz and EMC, which of course made us very vulnerable both to the sheer scale of our new competitors and to their potential ability to price us out of the market.

So this time we took the initiative and appointed a bank (Credit Suisse) to start the formal process of looking for potential buyers. We pitched to several interested companies (including at least one VERY BIG company) and fairly quickly reached a draft agreement with Veritas. It turned out that although they had gone ahead with the “build” option, it hadn’t worked out for them and this time we met people who were genuinely interested in acquiring the product for the right reasons.

The whole process proceeded quite rapidly from draft agreement to the completion of the acquisition in September 2004 with a purchase price of $225m plus our selling costs being met by Veritas.

Conveniently Veritas’s UK headquarters were in the same town, Reading, as KVS so the logistics of the move were very easy for the UK people, but of course this wasn’t necessarily the case in other countries.

Not long after we had completely rebadged and repackaged the products to Veritas, we had to do it all over again as Symantec in turn acquired Veritas. This also explained in retrospect why Symantec declined to talk to us during our acquisition process. This further rebrand then resulted in Enterprise Vault’s fifth corporate logo, and is its longest lived one to date.

Apart from the product itself, what remained consistent through this story is the engineering team. Many of those who were there to found KVS (and who had already been working together for several years at Digital) are still working on the product, as are almost all the engineers who subsequently joined us and who were there at the time of the acquisition. Any engineering departures have tended to be due to retirement rather than moving elsewhere. This is also true of quite a few of the technical staff in the field who are still working with the product.

Some of these technical experts have even started their own companies (such as Vault Solutions) based on Enterprise Vault support, services and add-ons. The fact that our start-up, having kicked off a new market, eventually spun off its own start-ups must be some sort of maturity milestone in itself.

What started as a niche business aimed at one particular target, Exchange email, broadened very rapidly in only a few years into a significant market sector with multiple companies and products that went much broader and deeper into the archive space. That growth has continued at a strong pace after the period that is covered here but that’s another story….

Leave a Reply